Why projects fail despite hard work is a question most project leaders never ask — because from the outside, everything looks fine. Meetings are full. Tasks are closing. The team is busy. And yet delivery still slips.

Most articles about why projects fail say the same things: poor planning, unclear scope, bad communication.

But they don’t explain the projects I’ve seen fail. The ones where planning was thorough, scope was documented, and the team was genuinely talented. The ones where everyone was working hard, meetings were full, and the task tracker was green — right up until it wasn’t.

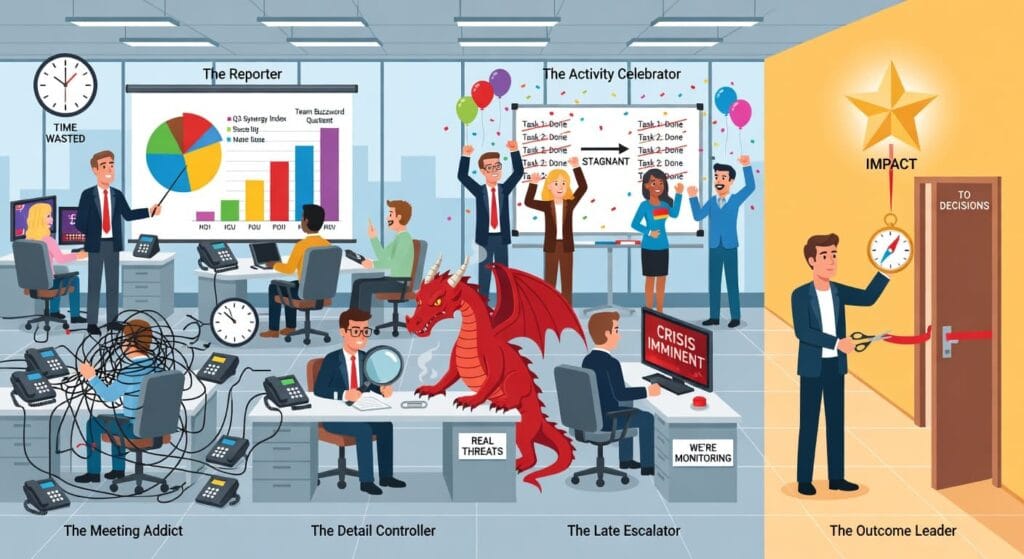

These are the projects that fail despite hard work. And in my experience, they fail because of a specific set of project management productivity mistakes that are almost impossible to see from the outside — because they look exactly like good project management.

Busyness doesn’t create results. It disguises the absence of them.

Here are six habits I have watched play out on real projects, with real consequences. These are the signs of poor project management that never appear in textbooks — because on the surface, they look like diligence.

1. Why Projects Fail: The Meeting Addict Has Too Many Meetings and Too Few Decisions

I worked with a project manager who had an instinct I came to recognise immediately: the moment an issue surfaced at site, his first move was to call a meeting.

Not to analyse the problem. Not to assess the options. To call a meeting — with all stakeholders involved — before he had even formed a view on what was actually wrong.

The logic, from his perspective, was reasonable. Get everyone in the room. Hear all sides. Align. But in practice, what happened was that an underprepared, multi-stakeholder meeting produced noise, not clarity. Then another meeting was called to consolidate the outcomes of the first. Then a third, because a key person had missed the second.

He moved from room to room. His calendar was always full. He was always in motion.

Did it improve productivity? Honestly — no. What it did was delay decision-making, diffuse accountability, and train his team to wait for a meeting before acting on anything.

The hard truth about a project manager with too many meetings is that they feel productive because they create visible activity. People talk. Notes are taken. Actions are assigned. But a meeting that produces no decision — where the output is another meeting — has consumed time without moving delivery.

Coordination is necessary. It is not sufficient. And when it becomes a default response to every problem, it signals something deeper: a leader who hasn’t yet developed the confidence to form a view alone before bringing the room in.

The link between meeting culture and leadership effectiveness is something I explored directly in Stop Being an Expensive Gofer as a Project Boss. If your calendar is always full and your project is still struggling, the two things are probably connected.

2. Why Projects Fail: The Activity Celebrator Mistakes Tasks for Progress

I have seen this pattern more than almost any other, and it is one of the hardest to challenge — because on the surface it looks like exactly what good project management should look like.

A project manager I worked with was meticulous about his schedule. Every task completion was logged. Every milestone closure was announced — sometimes with a team message, sometimes with a brief in the status meeting. He tracked progress obsessively and reported it with genuine pride.

Whether the project was ultimately successful? Not really.

The tasks being completed were real. The effort was genuine. But the celebrations were happening around activity that wasn’t on the critical path, or around milestones that looked complete on paper but had unresolved dependencies sitting quietly underneath them.

He was measuring motion. Not movement.

Busy teams can miss delivery — and do, regularly — because the activity metrics they celebrate aren’t the ones that drive the milestone. The question is never how much did we do. It is: did the needle move on the things that actually matter to delivery?

A project system built around milestone accountability — not task volume — is fundamentally different to operate. It is also far less comfortable, because it leaves nowhere to hide.

If you want to understand what that kind of system looks like in practice, How to Build Project Systems That Nail Deadlines is a good starting point.This is one of the most overlooked answers to why projects fail.

3. Why Projects Fail: The Reporter Sends Noise Instead of Signal

There is a particular kind of project manager who believes that detailed reporting to senior leadership earns credibility. That if the top team can see every moving part — every task, every risk entry, every contractor update — they will trust him more.

I watched one play this out in real time. His reports to leadership were comprehensive to a fault. Page after page of operational detail. Every subcontractor’s progress. Every minor schedule variation. Every procurement status.

What he didn’t understand — and what became painfully clear over time — was that information at that level of granularity is not useful to top management. It is noise. Leadership does not need to know the nuts and bolts. They need to know: are we on track, what are the threats, what decisions do they need to make?

Reporting at the wrong altitude doesn’t earn mileage. It trains leadership to stop reading your reports — and to stop asking you the questions that matter. Worse, it consumes time that should go toward synthesising the picture, not cataloguing the parts.

The discipline of reporting is not volume. It is signal. What is the headline? What has changed? What requires a decision? Everything else is context that should be available on request — not pushed upward by default.

This connects directly to the escalation problem, which I explore in Why Risks Derail Projects and How to Stop Them — the right information, to the right person, at the right time, is the discipline most reporting cultures never actually develop.

4. Why Projects Fail: The Late Escalator Turns Problems into Crises

This one is the most expensive habit I have seen on projects. And the most common.

A project I was close to had been accumulating overruns for months. The team knew. The project manager knew. But the belief — repeated often enough that it became almost official — was that there was still time for recovery. That the situation would stabilise. That escalating too early would create unnecessary alarm.

It didn’t stabilise. The overruns continued. And by the time the full picture reached senior leadership, the options were gone. What followed were disastrous write-downs that pulled the organisation’s results for that reporting period — consequences that could have been managed, or at least mitigated, if the honest picture had surfaced six months earlier.

Late escalation doesn’t happen because people are negligent. It happens because hope is more comfortable than honesty. Because admitting a problem feels like admitting failure. Because every week, there is a reasonable case for waiting just a little longer.

But delay is never neutral in project execution. Every week that an overrun, a risk, or a schedule breach sits unescalated is a week in which options narrow and costs compound. By the time it surfaces, what could have been a managed problem has become a crisis with no good exits.

This is one of the most damaging — and least discussed — reasons why projects fail despite good planning. The plan was fine. The execution was honest. But the truth didn’t travel upward in time.

The connection between escalation culture and schedule pressure is something I explore directly in EPC Project Scheduling Leadership: How to Challenge Unrealistic Timelines. The cost of delay is always higher than it looks in the moment.

5. Why Projects Fail: The Detail Controller Micromanages Instead of Leads

Delegation should create space. In practice, for some project leaders, it creates anxiety.

I knew a project manager who was genuinely capable — experienced, technically strong, well-regarded. When he delegated a task to his deputy, he did so formally and clearly. But he could not leave it there.

He tracked his deputy’s movements. He checked in constantly. He re-reviewed work that had already been reviewed. He inserted himself into decisions that had been explicitly handed over. His deputy, who was equally capable, found it impossible to operate. The micromanagement didn’t improve the work — it frustrated the person doing it and created a quiet but persistent tension that affected the whole team dynamic.

Did it improve project results? No. What it produced was a highly capable deputy who stopped taking initiative, because initiative had been repeatedly second-guessed.

The habit underneath this pattern is one I recognise as surprisingly common among high-performers who move into leadership: the inability to tolerate the discomfort of not being in direct control. The detail controller isn’t trying to undermine anyone. They simply cannot sit with uncertainty about work they feel responsible for.

But leadership requires exactly that tolerance. You cannot scale delivery through your own hands. You scale it through people — and people need room to operate, make decisions, and occasionally get things slightly wrong without being intercepted.

Attention is not the same as impact. Where you spend your attention as a leader is a strategic choice, whether you treat it that way or not.

What this looks like when it goes right — when leadership presence creates confidence rather than constraint — is at the heart of What Sets Top Project Leaders Apart Now.

6. What Good Looks Like — The Outcome Leader

The outcome leader is rarely the most comfortable person in the room.

They cut meetings that produce only updates. They force decisions when others prefer to wait. They surface risks early — before they’re certain, before the picture is clean, because they understand that early discomfort is cheaper than late certainty.

They delegate and mean it. They track outcomes, not movements. They report at the altitude their audience needs, not the altitude that makes them feel safe. And when something is going wrong — when the recovery narrative is starting to sound more like hope than plan — they say so, clearly, early, and to the right people.

They measure movement, not motion.

None of this is effortless. It requires a different relationship with discomfort than most of the habits described above. Outcome leadership means regularly doing the harder, less visible thing — and accepting that it won’t always look like busy, productive work from the outside.

But it is the work that actually moves delivery. And over time, on the projects that matter, that is the only work that counts.

Why Projects Fail Silently — And How to Stop It

Every habit described in this article is, in some way, socially rewarded. Meetings signal collaboration. Detailed reporting signals thoroughness. Task celebrations build team morale. Late escalation avoids creating alarm. Micromanagement signals commitment.

These behaviours fit organisational norms. They create visible activity. They don’t cause conflict. And in most professional environments, they go largely unchallenged — because everyone around them is doing the same thing.

That is exactly what makes them so damaging at scale.

When these habits become the culture of a project team, the project can look healthy for months while the real problems quietly compound. By the time the picture becomes impossible to ignore, the options available to fix it are a fraction of what they would have been at the start.

This is why projects fail despite hard work. Not because people weren’t trying. Because the effort was pointed at the wrong things — and nobody stopped to ask whether all that motion was actually creating movement.

The fix is not a tool or a framework. It is a deliberate decision — by leaders, individually and collectively — to measure themselves differently. Not by how busy they look. By whether the project actually moved.

Ultimately, why projects fail despite hard work is always the same answer — effort pointed at the wrong things, for too long, without anyone stopping to ask whether the motion was creating movement.

Key Takeaways

- Why projects fail despite hard work comes down to one thing — effort directed at visible, comfortable activity rather than outcome-critical decisions.

- A project manager with too many meetings and too few decisions is a delivery risk, not an asset

- Celebrating task completion while the milestone doesn’t move is motion, not progress

- Reporting volume to senior leadership without signal wastes their attention and erodes your credibility

- Late escalation transforms manageable problems into terminal ones — early honesty is a leadership discipline, not a risk

- Micromanagement doesn’t improve results — it frustrates capable people and creates the dependency it was meant to prevent

- Outcome leadership means tolerating the discomfort of doing less-visible, harder work — and being honest about what is really happening

FAQ

Why do projects fail despite hard work and good planning?

Projects fail despite hard work because the effort is often directed at visible, comfortable activity — meetings, reports, task completions — rather than the decisions and escalations that actually drive delivery. Good planning creates a roadmap, but execution fails when teams confuse motion with movement, delay honest escalation, or spend leadership attention on low-impact work.

What are the most common project management productivity mistakes?

The most common project management productivity mistakes are holding too many meetings without decisions, celebrating task activity instead of milestone movement, reporting operational detail to senior leadership instead of signals and decisions, escalating risks too late, and micromanaging delegated work. All of these look productive from the outside — which is precisely what makes them dangerous.

What are the signs of poor project management?

Signs of poor project management include a calendar dominated by status meetings with no decisions, reports that are comprehensive but trigger no action, milestones that look complete on paper but have unresolved dependencies, risks that surface late as crises rather than early as problems, and capable team members who stop taking initiative because they are constantly second-guessed.

Why does a project manager having too many meetings hurt delivery?

A project manager with too many meetings hurts delivery because meetings without decisions consume time without creating progress. When meetings become the default response to every problem, decision-making is delayed, accountability is diffused, and teams learn to wait for a meeting before acting. Coordination is necessary — but it is not a substitute for leadership judgment.

Why is late escalation so damaging in project management?

Late escalation is damaging because it eliminates options. Problems surfaced early can usually be managed within existing contingency. Problems surfaced late — because teams hoped they would self-resolve — often result in write-downs, emergency decisions, and consequences that were entirely avoidable. Every week of delayed escalation narrows the options available and increases the cost of recovery.

Does micromanagement improve project results?

No. Micromanagement consistently produces the opposite of its intent. It frustrates capable people, reduces initiative, creates dependency, and consumes leadership time that should go toward strategic decisions. Effective delegation means trusting the person and tracking the outcome — not monitoring every step of the journey.

What does outcome leadership mean in project management?

Outcome leadership in project management means making the decisions and creating the conditions that move delivery forward — not just keeping people informed and aligned. It involves cutting low-value coordination, forcing decisions under uncertainty, surfacing risks early, reporting at the right altitude, and holding the team accountable to milestone movement rather than activity volume.